Police officials have lobbied for the right to conduct a variety of unfettered electronic surveillance tactics on the public, everything from being able to affix GPS trackers on vehicles to acquiring mobile phone cell-site location records and deploying "stingrays" in public places—all without warrants.

Some law enforcement officials, however, are frightened when it's the public doing the monitoring—especially when there's an app for that. Google-owned Waze, although offering a host of traffic data, doubles as a Digital Age version of the police band radio.

Authorities said the app amounts to a "police stalker" in the aftermath of last month's point-blank range murder of two New York Police Department officers. That's according to the message some officials gave over the weekend during the National Sheriffs Association meeting in Washington.

"The police community needs to coordinate an effort to have the owner, Google, act like the responsible corporate citizen they have always been and remove this feature from the application even before any litigation or statutory action," Sheriff Mike Brown of Bedford County, Virginia, told the gathering, according to an account provided by The Associated Press. Brown, who chairs the National Sheriffs Association's technology committee, said the app's police-reporting feature renders it a "police stalker."

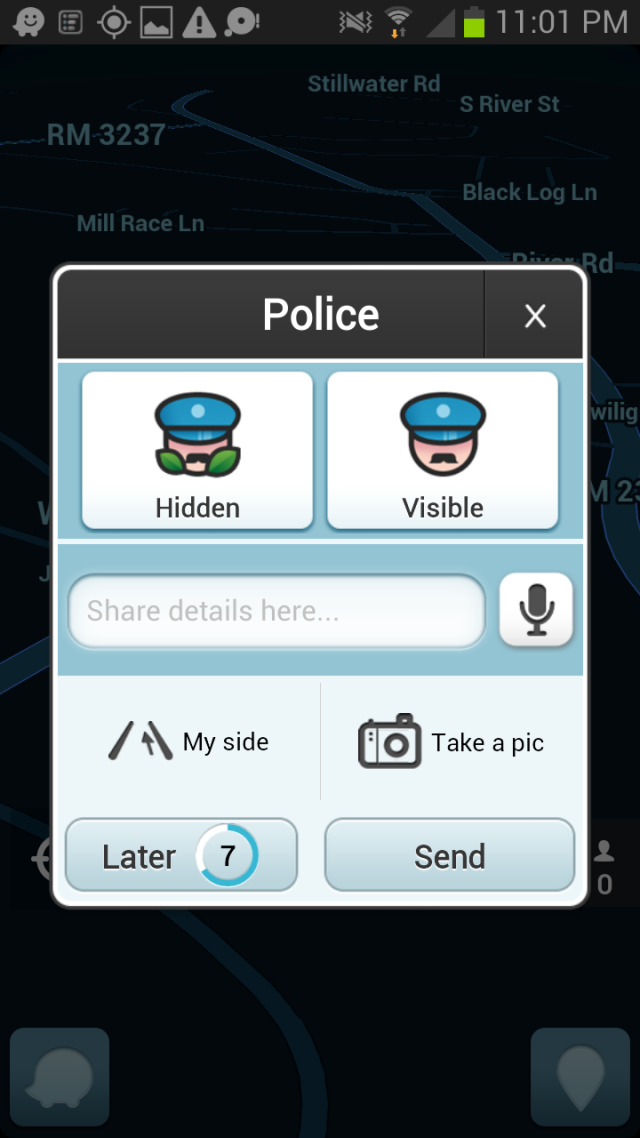

The app, used by some 50 million people in 200 countries, is a free service that provides real-time traffic data about accidents, congestion, traffic cameras, and weather among other information. It also allows Waze users to report a police presence, which then appears on a traffic map for others to see. The app provides no other data about the police's public presence.

"I can think of 100 ways that it could present an officer-safety issue," said Jim Pasco, the executive director of the Fraternal Order of Police. "There's no control over who uses it. So, if you're a criminal and you want to rob a bank, hypothetically, you use your Waze."

Waze spokeswoman Julie Mossler said in an e-mail that the app includes reports of police presence "because most users tend to drive more carefully when they believe law enforcement is nearby."

The police officials' comments came a month after two NYPD officers were killed as they sat in their patrol car. The assailant, who was shot dead, had posted to his Instagram a screenshot of Waze along with police threats. Police, however, do not think he used Waze to target his victims. Assailant Ismaaiyl Brinsley had abandoned his phone about two miles from the scene before he opened fire.

The attack on Waze comes amid a growing conflict about privacy in the modern age. Usually, that privacy interest concerns the general public's rights.

Consider that, just last month, lawmakers revealed that the Federal Bureau of Investigation was taking the position that court warrants are not required when deploying cell-site simulators in public places. Nicknamed "stingrays," the devices are decoy cell towers that capture locations and identities of mobile phone users and can intercept calls and text. The legal issue remains unresolved in the courts.

Also last month, a federal judge tossed evidence that was gathered by a webcam—turned on for six weeks—that the authorities secretly nailed to a utility pole 100 yards from a suspected drug dealer's rural Washington state house. The Justice Department contended that the webcam, with pan-and-zoom capabilities that were operated from afar, was no different from a police officer's observation from the public right-of-way.

Another privacy issue, meanwhile, is whether the authorities need warrants to acquire mobile phone users' cell-site location history. The government says no in one of the leading cases on the issue.

To be sure, the Supreme Court has held police powers in check in some high-profile digital cases. The court ruled unanimously last year that the authorities may not search the mobile phones of those they arrest unless they have a court warrant. In 2012, the justices said the police, generally, may not place GPS trackers on vehicles to follow their every move without warrants.

The government argued that a GPS tracker was constitutional because motorists have no expectation of privacy while in public.

reader comments

274