On September 19, there was a mob scene around a large glass cube at the corner of 57th Street and Fifth Avenue. Thousands of people stood in a mass, separated by rows of metal barriers. Camera crews looked on, recording the event. What might have appeared like civic unrest in another time or place was just business as usual at Apple’s flagship store during the release of a new product — in this case, the iPhone 6. The scene will almost certainly repeat itself in a few months when the new Apple Watches arrive.

Though it has been open for less than a decade, the Apple store under the glass cube at the base GM building is already one of the best-known and most successful retail sites in the world. But few people realize that it exists because of a real estate developer who had just taken the biggest gamble of his life, and needed to solve a problem — and because he knew just how to play mind games with Steve Jobs.

In 2003, when the still-aspiring property mogul Harry Macklowe finally hit the big-time with his purchase of the iconic GM Building for $1.4 billion in borrowed funds, one of his first concerns was how to fix the “problematic plaza,” as industry insiders and architects called the large and rather useless open space that extended from the front entrance to Fifth Avenue.

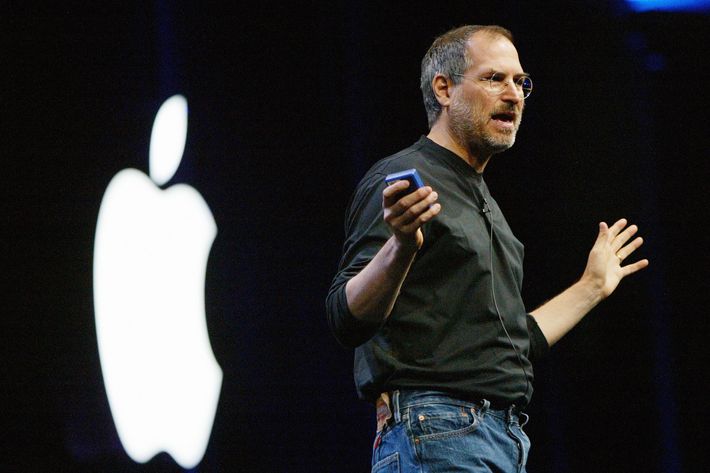

Macklowe had a feeling that his best bet for really transforming the property from a prestigious relic into a vibrant commercial property lay with Apple, which was on the verge of blowing up into a retail titan several years into Steve Jobs’s second stint as CEO. He pestered George Blankenship, Apple’s vice-president of real estate, until he was invited to a meeting with Jobs in November 2003.

Out in Cupertino, Macklowe hit it off immediately with Jobs. “He’s wearing this black turtleneck, he’s wearing black jeans … it was terrific. The Apple team started talking about a flagship store that would be groundbreaking in almost every aspect,” he said. “It would be open 24/7.” The meeting included Macklowe’s longtime design collaborator Dan Shannon and the architects Peter Q. Bohlin and Karl Backus from Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, the designers of the Apple Store in Soho.

What happened next has long been the subject of speculation and some dispute: Who came up the idea of placing a 30‐foot square glass cube — the world’s “smallest skyscraper” — in the middle of the GM Building plaza? In that lightbulb moment, an unused basement that had caused headaches for its owners for more than 40 years morphed into what is arguably the most famous retail space in the world.

The answer, according to four people in the room — Macklowe, Backus, Bohlin, and Shannon — is that the cube was the brainchild of the late Steve Jobs. “The point of the meeting,” Shannon recalled, “was that Steve wanted to show Harry what his vision was for that site. We got there and they had this beautiful wood model of the building and plaza, and there’s this 40‐by‐40‐foot glass cube in the middle of the plaza. And Harry knew immediately that that was the right answer. Our original ideas had the glass pavilion closer to the street, because the zoning laws required a street wall for that site. And the Apple team put it right in the middle, more like the Louvre. … Harry thought it was brilliant.”

Said Macklowe:“[Jobs] presented to me and I presented to him. … He had this cube, which was quite different from what you see there today, and I had a cube that was quite different from what we see today as well. It took us half an hour to make a deal.”

Macklowe knew that the only major flaw in Jobs’s concept was the size. Forty feet was too big — not just for zoning restrictions but for the scale of the building. No one would like it — not the city, not the tenants. He also knew that talking about it with Jobs wouldn’t get him anywhere. He’d have to show Apple what he meant. He invited Apple’s retail development executives, Ron Johnson and Robert “Rob” Briger, to the building two weeks after the Cupertino meeting, to view a scaffolding mock‐up of the cube — in the dead of night. (Regulations forbade Macklowe to build during the day.)

Around two in the morning, the group met in front of the GM Building. The 40‐foot cube was unveiled. They all agreed it was too big. It obscured the building. Macklowe was grinning. He then gave the signal, and the model was dismantled — only to reveal a 30‐foot cube he had secretly constructed underneath.

His magic trick worked. Apple was sold on the smaller cube.

Now Macklowe had to get approval from the city’s Planning Commission to put the cube in the middle of a simplified plaza. One of the ideas he was most proud of, he told the commission, he had “lifted” from the Place Vendome in Paris, where he had noticed tiny bollards in place to discourage skateboarders. He thought the bollards “just perfect” for his square.

Jobs phoned him. And phoned. And phoned. The Apple chief wanted continual updates. He even had Macklowe and Shannon visit Cupertino again, this time so they could all look at a stone for the plaza that Macklowe had found in Paris. Jobs created a mock‐up in the Apple parking lot. Macklowe felt that he and Jobs were becoming friends. He offered him an office in the building, but Jobs declined. “He said, ‘When I come to New York, I want to be in Soho. I want to be in Chelsea. I want to be surrounded by young people. … I can listen to what they’re thinking. I want to have new ideas.’”

For Macklowe to redesign the plaza and put retailers in the bottom of the building, some existing tenants had to be malleable — and mollified. He needed CBS to change camera angles for its morning show, which filmed on the ground floor; he needed the Lauders to relocate their company store; TPG Inc., the owner of the Bally shoe store, also had to move. “I did them favors; they did me favors,” recalls Macklowe. “I think we all felt we were doing something great. Leonard and Evelyn [Lauder] said [to me], ‘We can’t believe what it is that you’ve done, and it’s a pleasure to be in the building again.’”

Construction started around the base of the building where Macklowe lured, among other luxury tenants, Porsche Design. He was also busy reaching out to businesspeople he knew could afford higher office rents and whose reputations would only burnish the building’s brand.

On May 19, 2006, the Apple cube was unveiled at 32 feet. It immediately drew long lines of customers and tourists. There was the cube rising with a glass elevator and circular stairs taking the crowds to the basement beneath. It was such a mob scene that Rob Sorin, Macklin’s real estate lawyer, later kicked himself for not charging a higher “stop” or floor on the “percentage rent” of the store’s profits that Apple agreed to pay Macklowe. “Apple really had no idea what this store was going to do in business per year, and we negotiated the ‘stop’ at a level that turned out to be horrendously low. The first year they made a million dollars a day,” he says.

Still, it was worth it. The deal was the shrewdest investment of Harry Macklowe’s career. The groundbreaking number of customers — the store attracted 50,000 visitors a week during its first year — would dramatically enhance the building’s value and update its reputation. Though still known officially as the GM Building, many people now nickname it “the Apple Building.”

At the opening, Harry was joined by his wife Linda, who was beaming. “I remember the reception that they had on a beautiful spring day for the opening of the Apple Store,” says one of Linda’s best friends. “And that was like Harry’s defining moment. I’ve never seen the guy so happy. All of his friends, all of his colleagues were there. And this thing was just fantastic.” Harry Macklowe had arrived.

Excerpted with permission of the publisher, Wiley, from The Liar’s Ball: The Extraordinary Saga of How One Building Broke the World’s Toughest Tycoons by Vicky Ward. Copyright (c) 2014 by Vicky Ward. All rights reserved.