When Mark Shuttleworth founded Canonical in 2004, he made a promise to his staff: "You can count on me for two years."

The idea was "to get the team to relax" and focus on the newly created Ubuntu operating system. Shuttleworth wanted to eliminate the pressure of becoming a blockbuster business overnight.

He issued no ultimatums. And although Shuttleworth wanted Canonical to be self-sustaining, he didn't threaten to abandon Ubuntu if it lost money. "When we started, I told the team two years," he recently told Ars. "I didn't say, 'till it's profitable.' I said, 'You can count on me for two years. What I want to really see is evidence of a clear path to success and really interesting disruption.'"

Now nearly 10 years later, Canonical remains unprofitable. Shuttleworth is worth an estimated half-billion dollars, having made his fortune by creating a digital certificate authority that he sold to VeriSign for $575 million in 1999. Today, he continues funding Canonical from his own fortune.

The desktop will die without a mobile counterpart

Shuttleworth still isn't issuing any ultimatums over profitability to Canonical employees. In fact, he's increased the amount he invests in the company as it moves beyond its desktop and server businesses into the mobile phone and tablet market with Ubuntu Touch.

"I think the desktop on its own will die," Shuttleworth said, explaining that it must be paired with mobile success to embrace the shifting nature of personal computing.

Shuttleworth's original goal of challenging Microsoft's desktop dominance with a Linux-based operating system has come and gone, with Windows still holding nearly 93 percent of the desktop OS market and all Linux distributions combined having just a 1 percent usage share. So it's no surprise that Canonical isn't yet profitable.

What may surprise some people is that Canonical could be profitable today if Shuttleworth was willing to give up his dream of revolutionizing end user computing and focus solely on business customers. Most people who know Ubuntu are familiar with it because of the free desktop operating system, but Canonical also has a respectable business delivering server software and the OpenStack cloud infrastructure platform to data centers. Canonical's clearest path to profitability would be dumping the desktop and mobile businesses altogether and focusing on the data center alone.

"We could slice Canonical to something profitable pretty straightforwardly," Shuttleworth said. "We could slice down to the server or we could slice down to just OpenStack, and we'd be much smaller and we'd be profitable."

That, of course, is something Shuttleworth has no intention of doing. While he's known as a true believer in open source software, he has a larger vision of building a single platform that spans everything from phones and tablets to PCs, servers, and the cloud.

"In my mind the scope of the opportunity has grown and with it my willingness to invest," he said. "I'm interested in the type of disruption, in the idea that at some future date you could have an app running on your phone, that app could be an Ubuntu app, you could dock that app to a big screen, and it would then be an Ubuntu PC. The data for that could be processed in a cloud running an Ubuntu guest and that cloud could be running on an Ubuntu host. Now, I don't want to sound megalomanic. But I think that's a real possibility… That's a pretty extraordinary disruption, and to me the sum of the parts is greater than any single one of them."

Canonical is headquartered in the UK and has more than 500 employees in over 30 countries. It's a private firm and we thus don't get quarterly reports detailing its revenue and expenses. Canonical's revenue did hit almost $30 million in 2009, a sum Shuttleworth at the time said would be self-sustaining. Revenue has grown since—despite the fact that Canonical is an open source company and thus gives most of its software away. DueDil, a financial information service that aggregates the annual reports submitted by UK-based companies, puts Canonical's revenue as of March 2012 at £34.9 million ($54.2 million) and loss at £6.8 million ($10.55 million). A Canonical spokesperson told Ars that these numbers are specific to the UK and "not a representation of the situation of Canonical across our global operations."

Free software, but plenty of ways to make money

While users can download Ubuntu for free and put it on any PC or server they'd like (something you can't do with Microsoft's Windows or Apple's OS X), Canonical has several ways of making money off the operating system.

Businesses that use Ubuntu desktops internally can pay Canonical for technical support and protection against patent lawsuits "arising from your use of Ubuntu." Moreover, hardware vendors that sell PCs pre-loaded with Ubuntu pay Canonical for that right, and they work closely with the company to make sure the hardware and software work well together. The Chinese government is paying Canonical to develop a custom version of Ubuntu to shift the country away from Windows.

Home users don't typically pay Canonical, but a somewhat controversial deal with Amazon that puts shopping search results in the Ubuntu desktop search tool brings in some cash.

Shuttleworth would not say whether the desktop business on its own is making money. While the desktop is "obviously not super-profitable," there is a "bit of a race" between the desktop and server groups "as to which is more important to our top line," he said.

"I think folks in the States don't have a lot of visibility into the amount of diversity in the PC world outside of the US," Shuttleworth said. "But if you look across the major vendors, Dell, HP, Lenovo, one of them will ship more than 20 percent of their volume globally with Ubuntu this year. Another one has committed to do the same next year, and the third, we think, will head in the same direction sooner rather than later."

Canonical declined to say which of those is which, per its policy of not giving specific details of commercial partnerships.

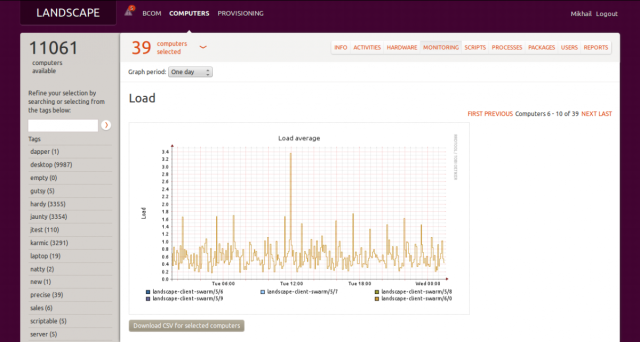

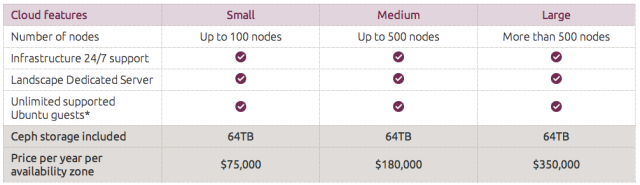

Canonical's server and cloud business has multiple revenue streams. The company sells support packages to businesses using Ubuntu Server and OpenStack. It also sells Landscape, a systems management tool for controlling Ubuntu desktop, server, and cloud deployments. Landscape is proprietary—while Ubuntu itself is open source, Canonical doesn't make the source code for all of its software freely available.

In addition to businesses that provide Ubuntu to their own employees, cloud vendors offer Ubuntu virtual machines over the Internet to anyone with a credit card. Canonical makes money each time you use an Ubuntu server in the cloud.

'You can download Ubuntu. We are quite happy to give it to you," Shuttleworth said. "But for a cloud vendor to turn around and offer Ubuntu because they're making representations on our behalf, essentially, it's a commercial proposition."

With the success of Amazon and other cloud services, that revenue source may not be small. "It is our goal to be the preferred way to deploy stuff on top of any cloud," Shuttleworth said. "And we are the #1 Linux on [Windows] Azure, we are the #1 operating system on Amazon, we're the #1 operating system, as best we can tell, on most of the public clouds that offer Linux."

Those companies offer Ubuntu as a guest operating system, but Ubuntu can also be used as the host, the operating system that allows the cloud to exist in the first place. Infrastructure-as-a-service clouds have been built with Ubuntu and OpenStack by the likes of AT&T, Deutsche Telekom, NTT, China Mobile, HP, Ericsson, and Rackspace.

OpenStack, an open source project, was developed by Rackspace and NASA, not Canonical. But OpenStack was built on Ubuntu, making it the software's default operating system. OpenStack itself is changing the way IT hardware is deployed, Ubuntu Cloud VP Kyle MacDonald told Ars at the Interop IT conference in Las Vegas three months ago. "Scaling is not by server anymore. It's literally by data center," MacDonald said. (Separately, MacDonald said Ubuntu has about 22 million users worldwide, based on the number of desktop and server installations that get security updates from Canonical systems. The majority of those are desktop users.)

OpenStack is still in the early adoption phase, with first movers often being highly technical institutions like CERN, operator of the Large Hadron Collider. Most OpenStack clouds today are likely prototypes and proofs of concept rather than paid deployments.

Yet "six or seven of the world's biggest telcos currently have Ubuntu OpenStack clouds in operation," Shuttleworth said. Some of them "are on firm commercial terms," and others are "finalizing the terms of an engagement." Even better, these are the same types of companies that could partner with Ubuntu to bring mobile phones to market.

reader comments

128