Ever since the National Security Agency's secret surveillance program came to light three weeks ago, implicated companies have issued carefully worded statements denying that government snoops have direct or wholesale access to e-mail and other sensitive customer data. The most strenuous denial came 10 days ago, when Apple said it took pains to protect personal information stored on its servers, in many cases by not collecting it in the first place.

"For example, conversations which take place over iMessage and FaceTime are protected by end-to-end encryption so no one but the sender and receiver can see or read them," company officials wrote. "Apple cannot decrypt that data. Similarly, we do not store data related to customers’ location, Map searches or Siri requests in any identifiable form."

Some cryptographers and civil liberties advocates have chafed at the claim that even Apple is unable to bypass the end-to-end encryption protecting them. After all, Apple controls the password-based authentication system that locks and unlocks customer data. More subtly, but no less important, cryptographic protections are highly nuanced things that involve huge numbers of moving parts. Choices about the types of keys that are used, the ways they're distributed, and the specific data that is and isn't encrypted have a huge effect on precisely what data is and isn't protected and under what circumstances.

Even when everything is done right, there are frequently limitations—and more often than not, huge trade-offs—on how easy the service will be to navigate by average users. And yet, none of this complexity is reflected in Apple's blanket statement. No wonder some security experts are skeptical.

I spent the past week weighing the evidence and believe it's an overstatement for Apple to say that only the sender and receiver of iMessage and FaceTime conversations can see and read their contents. There are several scenarios in which Apple employees, either at the direction of an NSA order or otherwise, could read customers' iMessage or FaceTime conversations, and I'll get to those in a moment. But first, I want to make it clear that my conclusion is based on so-called black-box testing, which examines the functionality of an application or service with no knowledge of their internal workings. No doubt, Apple engineers have a vastly more complete understanding, but company representatives declined my request for more information.

Passing the mud puddle test

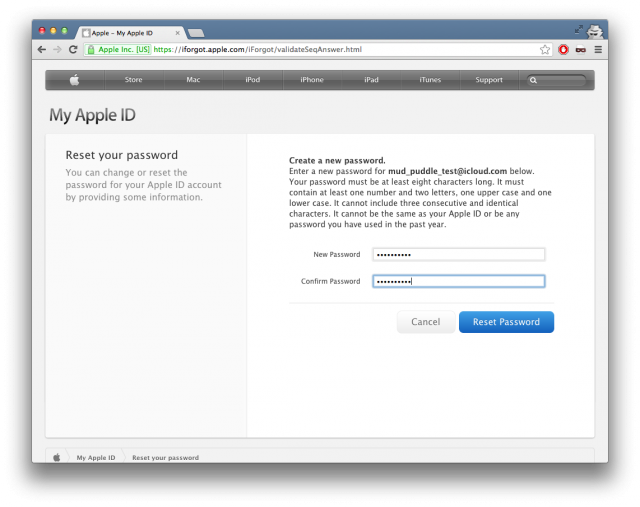

The first important exception to the claim that Apple can't read iMessages is that it doesn't apply if those conversations are stored as a backup in a user's iCloud account. How do cryptographers know this to be true? Because iCloud encryption doesn't pass what Johns Hopkins University research professor Matt Green calls the mud puddle experiment, a litmus test for assessing the security of cloud encryption protections. At its core, it involves the user losing the iPhone containing his data, changing his iCloud password, and then attempting to restore the data onto a new device. If the user can retrieve the data, so too can the cloud provider, either by a rogue employee with the authority and know-how or at the behest of the government.

At my request, independent privacy and security researcher Ashkan Soltani performed the mud puddle test earlier this week and confirmed that it's possible for Apple to decrypt iMessages stored in the Apple cloud in just seconds or minutes. After answering several security questions to reset his iCloud password, he tried to restore his backup to a completely different iPhone that had been reset to a factory-clean state. The backup data—including iMessages, e-mail, and photos—were restored in full to the new device.

"A preliminary black-box test seems to indicate old iMessages, text messages, and e-mails are stored in iCloud and can be restored using the iForgot mud puddle recovery test," Soltani said. "It definitely appears that iMessages are restored from iCloud backup, not the iMessage service."

Green, the Johns Hopkins cryptographer, was able to reproduce those results in his own test. He said it's technically possible Apple uses security questions to encrypt the iCloud backups, and if this were true, it would strengthen the claim that it's not possible for people other than the sender and receiver to read messages. But Green went on to say it's not likely that security questions are being used to derive an encryption key, since the answers don't contain enough entropy to securely encrypt the data.

The take-away: true end-to-end encryption doesn't apply to iMessages backed up in iCloud. If you want to ensure your iMessage conversations aren't susceptible to government surveillance, don't store them there. Ever. Some people may already have been aware of this important limitation, but since I can't find any place where Apple has explicitly spelled it out, it's worth including the caveat in this article.

Keys to the Kingdom

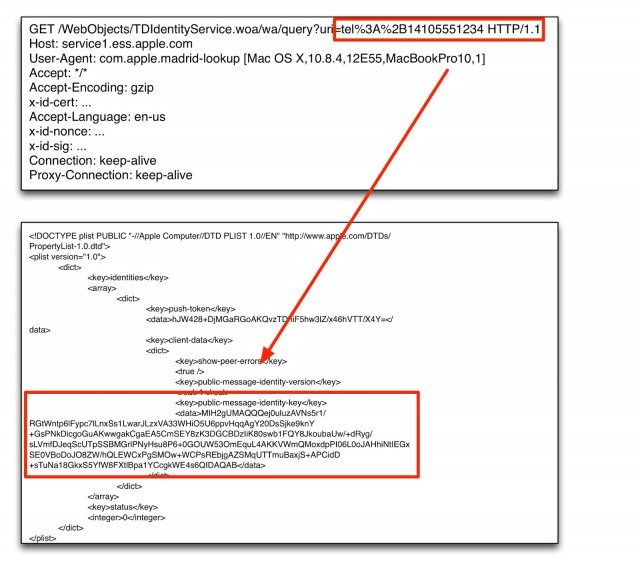

But even if you don't store iMessages in iCloud, there are almost certainly other ways Apple could decrypt them if it wanted to. That's because Apple acts as a directory look-up service that iMessage apps can use to find the public key belonging to the person receiving a message. The integrity of the entire system rests on Apple distributing the right public key for the right person. The ease in resetting passwords already suggests Apple has little trouble generating new user credentials. And there doesn't appear to be any warnings or dialogs displayed when the public key of a receiver has changed.

The upshot is that Apple employees—or maybe even an attacker who hacks Apple's directory server—might be able to alter the key distribution mechanism, swapping out a receiver's public key with whatever key the employees or attackers choose. Whoever has the corresponding private key could then read the messages.

"message identity key" associated with a modified iPhone phone number. Cryptographers say it's possible Apple could easily change the key that's delivered.

There's also the ability to display sent and received iMessages on multiple devices, so that a user can easily view conversations whether she's using her Mac, iPhone, or iPad. No doubt, this makes life more convenient, but it also could diminish the encryption protection. Right now, iMessage appears to notify users when a new device is configured to receive messages, but there's no indication these warnings are hard-wired into the system. If they're not, then Apple can turn them off at will. And with the notifications suppressed, it would be possible for a new device belonging to someone other than the account holder to secretly receive iMessage communications. While this technique would most likely work only for messages sent and received after the new device was silently added—and not messages sent or received months or years earlier—it still seems to highlight a significant loophole to the claim that even Apple can't decrypt iMessage conversations.

And as Green makes clear in his blog post, Apple's statement says nothing about how company officials handle metadata showing, for example, the times messages were sent and who received them.

Keeping them honest

None of this discussion is intended to single out Apple. Judging from the difficulty some federal agents have monitoring suspects' iMessages, the instant messaging service is probably one of the harder ones to tap. But hard to decrypt, and impossible to decrypt are two entirely different things. Ultimately, I decided to publish this article because Apple is the only company to step forward following revelations of the NSA's PRISM surveillance program and suggest it's technically infeasible for third-parties to read or decrypt its encrypted data.

There's also some historical reason for viewing the Apple denial with skepticism. In 2008, officials with the Skype VoIP service told CNET they're unable to comply with wiretap orders. Last week, Microsoft officials—who have since acquired the VoIP service—declined to affirm that such claims are still true. The Apple denial, some critics say, may be following a similar strategy.

"In the case of iMessage intercept capabilities, Apple is taking a page from Skype's playbook—make very carefully worded statements about the existence of encryption, and then let people read far more into their claims than they have actually made," Chris Soghoian, who is principal technologist and senior policy analyst for the American Civil Liberties Union, told Ars. "When reading Apple's carefully worded PRISM denial, remember it was written by a hybrid team of lawyers and PR folks. Every word matters. At best, they are being cagey, at worst, outright deceptive."

As Soghoian and other critics admit, the end-to-end encryption included with iMessage may make it impossible for Apple to decrypt conversations, at least in some circumstances. But in the absence of key details that Apple has steadfastly declined to provide, customers who are especially concerned about their privacy would do well to assume otherwise.

reader comments

88