By now, you've probably heard the story: exemplary student Andrea Hernandez has decided to fight her San Antonio high school's plan to outfit every student with an RFID-equipped badge in order to better take attendance and track students while on school property. (Radio frequency identification tags are short-range tracking tags that can be scanned by local readers, though they don't enable any sort of GPS-style location tracking of a student's movements around town, at home, etc.) Hernandez objects to the plan, which the district instituted in order to better recover its daily per-pupil funding from the state of Texas, on the grounds that it was a terrific invasion of her privacy—and of her religious liberty.

How can a plastic badge with a tiny built-in microchip violate religious liberty? The Rutherford Institute, which has taken the Hernandez case and filed a lawsuit (PDF) over it in Bexar County, Texas, puts it this way:

Plaintiff and her father object to the requirement that Plaintiff wear the Smart ID badge on the basis of Scriptures found in the book of Revelation. According to these Scriptures, an individual's acceptance of a certain code, identified with his or her person, as a pass conferring certain privileges from a secular ruling authority, is a form of idolatry or submission to a false god.

The hugely broad definition offered here would seem to sweep up many things, including my children's annual city pool passes, but what's actually being discussed is something more specific: the Mark of the Beast.

The hundreds of news stories on the controversy have focused largely on the privacy element, though some have repeated the Mark of the Beast claims without much in the way of explanation. Many Ars readers, encountering the story for the first time, might well have shared some of the privacy concerns expressed by Hernandez, but come up short in understanding the reason for her objection. What is this mark, and why has it been so tied to certain specific forms of technology? Why do RFID tags and bar codes, in particular, arouse such concerns? And did "John the Revelator" really record long-ago prophecies about contactless payment solutions and geolocation?

Good questions.

A long and very strange trip

A great aunt of mine (Nate) once sent my entire family on a two-week tour of Europe's greatest hits. Those who have been on such tours will recognize the type: expensive international hotels in city centers at night, lengthy bus trips down Europe's finest stretches of tarmac during the day, all in order to make it from London to Rome and back to Paris within 14 days. The bus portions of the trip were not specially remarkable for anything other than epic card games—except for the moment when we pulled out of Brussels one morning on our way to points further east.

Our tour guide pointed to a set of European Union buildings in the distance; just behind me, an older man turned to his wife and announced that these were the buildings in which an infamous computer called the BEAST resided, ready and waiting to be put to the use of the Antichrist after he had turned the EU into the dictatorship that would eventually bring us all to the apocalypse and thus to the utter end of the world. This computer would apparently be responsible for tracking us all and our payments, and it would freeze the true believers out of the global commerce stream. His wife did not appear to think this was an unusual thing to say, and she continued to film the roadside scenery with her video camera.

And it was not actually such an unusual thing to say if you came of age within American evangelical and fundamentalist circles during the 20th century—most particularly the '70s and '80s. These were true golden years of apocalyptic, Mark of the Beast, Antichrist-driven thinking. Famous nonfiction books like The Late Great Planet Earth translated the fascinating apocalyptic imagery of the Bible into blueprints for impending doom, matching cryptic ancient words to concrete contemporary events. In this view, the world was likely to end soon-ish—quite possibly within 20-50 years—at which point the Second Coming of Jesus Christ would bring about the creation of a new, remade world for humanity. Before that happened, though, there would be suffering, as the power of the Antichrist waxed and the power of Christians in the world waned (most having been raptured before the final "Great Tribulation" began).

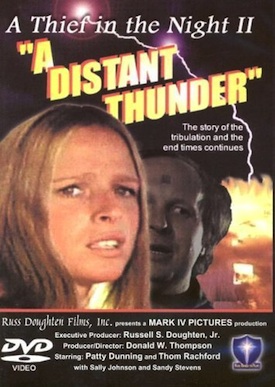

This set the background for a thousand Christian youth group meetings throughout the 1980s, in which kids watched films like 1972's A Thief in the Night or 1978's Distant Thunder, the latter perhaps the most classic late-'70s apocalypse flick. Short version of Thunder: everyone left after the rapture eventually gets rounded up if they don't take a special mark on their foreheads. Those who refuse the mark are ushered into a back room, after which many come out screaming and accept the dotted pattern on their skin. What's in the horrible room that can shake the new faith of those "left behind" after the rapture? SPOILER ALERT: it's a guillotine. (Skip to the 6:50 mark in the clip below to get the flavor.) Those who take the Mark of the Beast are spared, of course—though their souls are doomed. You can still buy the film on DVD from Amazon (sold by "armageddonbooks," naturally) for $26.95.

This basic view of the world's end saw perhaps its greatest cultural breakthrough into the mainstream with the 1990s "Left Behind" series, which included original books, children's books, audiobooks, nonfiction books, military books, movies, video games, background wallpaper, screensavers, etc, etc.

With all of the attention some Christians have given the Mark of the Beast throughout the centuries, the phrase appears only once in the Bible, as part of the last book of the Christian New Testament, the Revelation of John. While apocalyptic passages exist in books of the Hebrew Bible like Daniel and Ezekiel, Revelation is the single book where the genre predominates.

Apocalyptic literature is defined by biblical scholar John J. Collins as "a genre of revelatory literature with a narrative framework, in which a revelation is mediated by an otherworldly being to a human recipient, disclosing a transcendent reality which is both temporal, insofar as it envisages eschatological salvation, and spatial insofar as it involves another, supernatural world."

This type of literature most often appeared when the faith community was under some sort of duress, whether it involved the remnant of Israel living in Babylonian captivity (as was the case with Daniel) or the early Christian church being persecuted by the Roman Empire (as was the case in the late first century when Revelation was written). The key message: live faithfully even under the thumb of your enemies—not necessarily because the Lord will return to bust open a giant can of Smite Thee on them some day, but because God's justice will eventually prevail and the good guys will win in the end.

Being apocalyptic in nature, one of Revelation's concerns is to reveal "the truth about unseen present realities… and unknown future realties, such as judgment and salvation," as Michael J. Gorman, author of Reading Revelation Responsibly: Uncivil Worship and Witness: Following the Lamb Into the New Creation, puts it. Likely written around 95 CE, much of the book is devoted to fantastic images: a scroll with seven seals, seven trumpets that sound, a final battle on the plain of Megiddo ("Armageddon"), and—most germane to our purposes—one dragon and a pair of beasts.

Two beasts, one mark

The dragon shows up in chapter 12 and is identified as Satan (literally "the adversary," a figure who opposes the followers of God). Shortly after the dragon's dramatic appearance, a beast arises from the sea. It has seven heads and 10 horns and is given power and authority by the dragon so that humankind will worship it. (The first beast is often identified as the Antichrist, although the term does not appear in Revelation.)

After the first beast wages war upon the faithful, a second beast appears on the scene, this one having two horns like a lamb and emerging out of the earth to promote the worship of the first beast. Think of him as the first beast's more charming PR flack.

Many biblical scholars see the dragon and two beasts of Revelation 13 as an unholy parody of the Christian trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit), but for our purposes, we're interested only in the second beast, the one who has the bright idea of marking people.

Also it [the second beast] causes all, both small and great, both rich and poor, both free and slave, to be marked on the right hand or the forehead, so that no one can buy or sell who does not have the mark, that is, the name of the beast or the number of its name. This calls for wisdom: let anyone with understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a person. Its number is six hundred sixty-six.

Revelation 13:15-18 (New Revised Standard Version)

It’s this section that has caused no small part of consternation for some fundamentalist and evangelical Christians over the past few decades. Those preoccupied with divining the hidden secrets of Revelation and Christian eschatology—the study of the end times—generally adhere to an interpretative scheme described as "premillennialist." They attempt to map the fantastic visions and imagery in Revelation to specific present and future events. We’re not going to go into detail into Christian eschatology—though we did offer a high-level overview of the concepts in our 2006 review of Left Behind: Eternal Forces.

That approach to Revelation and to the world can see technological advances in particular as something to be feared, especially because the Mark of the Beast sounds more than a bit like electronic tracking and payment systems of today. Implanted NFC ID/payment chips? RFID tags? Bar code tattoos? It's all technically possible.

But the line that calls for "wisdom" remains far more mysterious.

reader comments

335