Back in 2005, we charted 30 years of personal computer market share to show graphically how the industry had developed, who succeeded and when, and how some iconic names eventually faded away completely. With the rise of whole new classes of "personal computers"—tablets and smartphones—it's worth updating all the numbers once more. And when we do so, we see something surprising: the adoption rates for our beloved mobile devices absolutely blow away the last few decades of desktop computer growth. People are adopting new technology faster than ever before.

Humans are naturally competitive creatures. Not only do we compete with each other for money and power, but we form strong allegiances to various tribes. Whether it's a favorite sports team or a chosen computing platform, we passionately cheer when they win and feel a punch in our guts when they lose. Companies know this, and they will trumpet their successes and quietly hide their failures. But is it any more important to want one multi-billion dollar company to win over another than it is to root for one arbitrary multi-million dollar athlete? Is it anything more than cheerleading?

Well—there's certainly plenty of cheerleading, but tracking the rise of fall of market share over time has more serious uses, too. Software developers need to keep track of market share so they can decide where to invest their resources. Consumers may then choose platforms based on software availability. Platforms can live—and sometimes die—by market share. The successes and failures of one generation of platforms affect the next, and ultimately this has an impact on everyone's digital lives.

Certain lessons from the past can also be applied today, and may even foreshadow what the future holds.

So what is market share?

Market share is typically defined as the percentage of a company's product compared to the total of all products sold in that category over a given period of time. For example, if Pepsi sold 25 percent of all brown carbonated soft drinks in the third quarter of 2010, it would be said to have a 25 percent market share for that quarter.

This sort of measurement works well in the beverage industry. The product is inherently disposable and shifts in market share are small. When you move from carbonated sugar water to the computer industry, as former Apple CEO John Sculley did in 1985, things get considerably more complicated.

In addition to market share, there's the concept of installed base. For computers, this would be the ratio of one brand or platform that is currently in use compared to the total number of computers in existence. This gets a lot trickier to calculate, because computers are being retired all the time at uneven intervals, and the time they spend being used is also highly variable. Still, it's an important thing to consider for computer companies, especially if they are trying to break into an already-established market. It's great if you have a ten percent market share in the first quarter that you sell your new product, but what if the industry has been around for years and countless millions of a competitor's devices already dominate the landscape?

Many articles on market share confuse the two terms. Some report on installed base using surveys of small groups of users, or look at the server logs of a few websites, and then announce this as market share. Neither of these two methods is especially accurate, and can sometimes produce questionable conclusions. The only reliable way to measure market share is to painstakingly count up all the sales of every product in a single quarter (this article will primarily use this method).

The other place where confusion can reign is in cherry-picking the regions used to provide the data. Companies with dwindling global share will often point to countries where their sales are still strong, or report only retail sales if their direct channel isn't doing as well. To be fair to everyone, the numbers I am using are for worldwide sales through all channels. With that said, let's begin by returning to the early days of the "personal computer" revolution.

The personal computer (Triassic Period)

We tend to forget that the personal computing industry, a cornerstone of the modern world that sells hundreds of millions of units every year, was largely created by a few disaffected nerds in their garages. Established mainframe and minicomputer companies took years even to notice the personal computer. When they finally entered the market, they had decidedly mixed results.

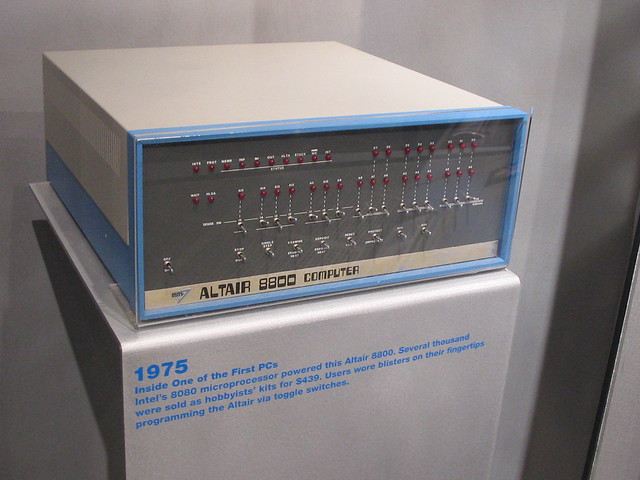

The first true "personal computer" was the Altair, invented in 1975 by Ed Roberts. It established most of what came to define the industry: the desktop form factor with attached peripherals, an internal expansion bus for add-on cards, a third-party software ecosystem with Microsoft providing the primary user interface (which in those days was a BASIC interpreter), and various conventions and computer fairs where users and vendors could meet.

Because anyone could enter the market with very little startup cost, the early years of the personal computer featured a dizzying array of models. I once took a copy of a 1980 issue of Computers & Electronics and counted over a hundred different incompatible machines advertised inside. This Wild West landscape couldn't last for long. Most early companies failed to make the transition from garage to global business.

Four winners emerged from this early era: the Atari 400/800, the Radio Shack TRS-80, the Commodore PET, and the Apple ][. The latter was in last place for the first few years, until a happy accident gave it the industry's first killer app: the spreadsheet VisiCalc. The PET soon gave way to the VIC-20 and the enormously popular Commodore 64, the first personal computer to really make an impact on the mass market. It would go on to sell 22 million units, which would still be a respectable number for a single new computer model today.

The early market was also much more regional than it is now. The Sinclair ZX-80, ZX-81, and later the Spectrum sold well in their native United Kingdom, but made a smaller dent in the US. Similarly, the Apple ][ sold in much smaller numbers in Europe. The UK had its own unique ecosystem of computers, including the popular BBC Micro, branded after the national broadcaster.

The young industry was shaken to the core when IBM introduced its own Personal Computer in 1981. The IBM PC, Model 5150, wasn't particularly impressive at launch. It was expensive, and while it did sport a 16-bit CPU capable of addressing up to 1MB of memory, it was underpowered, had no graphics capabilities out of the box, and had no sound chip. Compared to a much cheaper and more colorful Commodore 64, it hardly seemed like a contender.

Two things changed the fate of the IBM PC: the IBM brand name and the clones. Ironically, the PC was easy to clone mostly because it was so uncomplicated, and it was uncomplicated because it had been hastily designed from off-the-shelf parts to get to market before some other computer maker took the market away from IBM forever. It had no custom chips, just a CPU hooked up to some RAM and an expansion bus that was fully documented so that third parties could create add-on cards. The only proprietary bit was a simple chip containing the BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) code that started the machine up and told all the parts how to communicate with each other. Even the operating system was off-the-rack, a hasty CP/M clone purchased by Microsoft.

Competition between the clones brought the price of the PC down, and add-on cards filled the gaps in functionality from the original model. The market story from 1981 to 1985 is largely about the PC—and we could call it a single market because the clones were absolutely, 100 percent compatible—slowly taking more and more market share. Other platforms, including the venerable Commodore 64, fell off.

reader comments

163