In his strange third-person memoir, Youth, JM Coetzee writes of his days as an employee of IBM in London in the early 1960s and his gradual inculcation into the corporation's culture. "THINK is the motto of IBM. What is special about IBM, he is given to understand, is that it is unrelentingly committed to thinking… Employees who do not think do not belong in IBM, which is the aristocrat of the business machine world." In fact, Coetzee swiftly discovers that his job is plodding and predictable, full of form-filling and repetitive tasks. Furthermore, "there is something about programming that flummoxes him". One interesting thing about Youth is that it illustrates how a bookish young man with a passion for Ezra Pound and Ford Madox Ford could be drawn into the world of technology. For all his disillusionment, Coetzee shows us the excitement that fizzed around the birth of computing some 50 years ago.

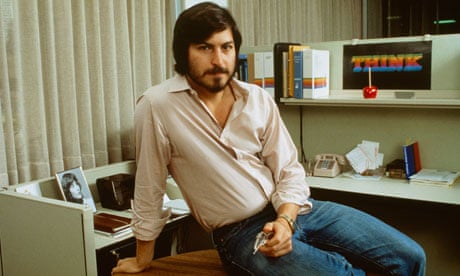

The Apple Revolution presents itself as doing something similar: looking at how a business empire such as Apple could spring out of the hippy idealism of 1970s California; how the long-haired, yoga-practising, deodorant-avoiding Jobs could rise to be one of the leading lights of modern capitalism. Given that Walter Isaacson's excellent if hagiographic Steve Jobs: The Exclusive Biography covered the life of the man in painstaking detail, a work examining the company's cultural heritage and looking at how its libertarian, principled ethos was gradually chiselled away might seem an interesting angle on the Apple phenomenon.

Slavoj Žižek, in Violence – his analysis of the brutality at the heart of capitalism – identifies "liberal communists" as "counter-cultural geeks who take over big corporations". He looks at the role of the hackers – once subversive and anti-establishment – and how they were co-opted into the capitalist system through a kind of corporate doublespeak that allowed them to marry their liberal, egalitarian ideals to the cold machine of the market economy. He doesn't mention Jobs by name, but the description of the "liberal communist" fits the Apple founder neatly: "Liberal communists do not want to be just machines for generating profits. They want their lives to have a deeper meaning. They are against old-fashioned religion, but for spirituality, for non-confessional meditation." Jobs, remember, could fit his legs behind his head. The only book he downloaded on to his iPad? Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda.

Žižek identifies these "liberal communists" with industrial barons of yesteryear such as Andrew Carnegie, who "employed a private army brutally to suppress organised labour in his steelworks and then distributed large parts of his wealth to educational, artistic and humanitarian causes". The "liberal communist" is more threatening than the sharp-suited Goldman Sachs banker precisely because he is shape-shifting, slippery, using the language and semiotics of the counter-culture while firmly upholding the establishment, raking in billions with one hand while getting on stage with Bono (who, ridiculously, called Jobs "the Elvis of the kind of hardware-software dialectic") to lament the world's poor.

If it has taken me rather a while to come to the book in question, that is because Luke Dormehl's readable, genial account of the rise of Apple doesn't do what it says on the tin. How I longed for Žižek's rapier mind to pick apart the cultural symbolism of the company's evolution from a weekly meet-up of Bay Area geeks ("I was not very socially adept," says one of them) called the Homebrew Computer Club to the world's biggest company with a market capitalisation of more than half a trillion dollars. I hoped for a genealogy of the "liberal communist", an explanation of the great betrayal that twisted hippy counter-culture into a tool of the corporate elite.

Unfortunately, The Apple Revolution simply doesn't give us enough analysis of what was happening outside the corporation. The reader, like many of those who worked for Apple, feels cut off from the real world, suspended in a cultural vacuum inside the walls of the company's Cupertino, California headquarters. Dormehl offers a compelling and painstakingly detailed account of the internecine squabbling that the company's hothouse atmosphere encouraged (and that forced Jobs to take a decade-long hiatus from the company he'd founded). He demonstrates Apple's unique approach to product development, illustrated by some nice anecdotes such as the technician who tracked air circulation in the Mac III by holding a lit joss stick under the machine, or the phone hacker employed by the company who patched through a prank call to Richard Nixon to demonstrate his skills. We also get a rather laboured account of the creation of the company's logo, including the fact that the original design was a Victorian woodcut with a quote from Wordsworth's The Prelude underneath it: "a mind forever voyaging through strange seas of thought, alone".

Early on in the book there is an attempt to look at the dichotomy that explains so much of the company's identity (and Jobs's personality): the pull between hippy idealism and capitalist money-hunger. Dormehl states rather bluntly that "although companies like Apple have continued to wave their world-changing ambitions over the years, no ideological problem exists with the notion of profiting from that new world order", and that "the voices of the counter-culture, musicians like Jobs's beloved Dylan, were churning out the soundtrack to a revolution while being paid multimillion-dollar sums by major record labels". But these explanations are presented flimsily, summarily, and we are soon back inside the world of Apple, with the blinds drawn.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion