As much as we love technology, it can also be a downer. With every bad gadget purchase, however infrequent, we're reminded that chip-based life forms are cold and indifferent. A touchscreen insists you tapped a full inch to the left from the icon you meant to hit; a laptop spins up its fan as the hard drive refuses to yield a Word document; a voice recorder drains its 4 AAs, dabs the corners of its lips, and dies for the third time today.

Gadgets that stubbornly refuse to operate the way the manual, advertisements, packaging, or marginally competent salespeople said they would should not be suffered in silence. Here, we exorcise the technological demons that have brought us serious gadget pain over the last few decades.

The 3Com Ergo Audrey, by Sean Gallagher

About the same time 3Com was preparing itself for the scrapheap of history by spinning off its Palm division, the company decided to get into the Internet "appliance" business. Its first and only attempt was the Ergo Audrey, a cute little Internet terminal styled like a retro-futuristic television, complete with a translucent stylus that stuck in the top of it like an antenna.The Audrey was an attempt to bring what the company called the "Web lifestyle" to the kitchen counter—giving busy families a place to sync up their Palms, check e-mail, leave scribbled electronic notes, and generally live life as any millennial version of the Jetsons would, minus the robot dog and maid. I never met anyone who actually lived like that in 2001, which might have been a sign that the Audrey was in trouble.

As cute as the thing was—it came in a palette of kitchen-friendly colors that included "sunshine" and "meadow," and was sponge-cleanable—it was particularly pointless for something that cost almost as much as a real PC. Once you paid $60 extra for the USB Ethernet adapter to get it hooked to broadband, it had one USB port left for a Palm or a very select set of compatible Canon printers. It had a Compact Flash port, but that couldn't be used for storage. Its e-mail client couldn't handle anything over 400k. It had 32MB of RAM—and that was it. There was a knob on the front for Web "channels," websites built by 3Com's friends at ABC and other companies who were somehow convinced to format them just for the Audrey.

Fortunately, I got mine back in the box to 3Com before they euthanized the whole line just seven months after launch. You can still find them for $50 or so on eBay if you want to look at what the future used to look like. But even the hardware hackers have gotten tired of them by now.

Broderbund U-Force NES controller, by Kyle Orland

The TV advertisement was badly lit and incredibly jumpy, but after watching it roughly one million times during reruns of Wild & Crazy Kids, eight-year-old me was pretty sure he could tell that the U Force was the greatest thing ever invented. Look, that guy's holding his hands like a steering wheel to control Rad Racer! Look, he's actually punching the air to make Little Mac punch in Punch-Out!! Even though Back to the Future told me I shouldn't even have to use my hands, and the U-Force required you to use your hands, I could tell this was the future of video games.

It cost me $60 of allowance money (which adjusting for kid-allowance inflation is worth about 10 bazillion dollars today) to learn that advertisements don't always represent reality completely accurately. Yeah, I could turn the car in Rad Racer, but only if I held my hands incredibly still in front of me and shifted them right when I wanted to turn. Yeah, using real punches in Punch-Out!! was fun, but the controller was way too slow and finicky to allow for reliable dodging, even against a pathetic opponent like Glass Joe.

Plus, waggling your arms to do every little thing in a game was pretty tiring and annoying. At least with modern motion-controlled games for the Wii or Kinect, designers know this and can try to design around it, preferably with frequent breaks. With the U Force, I learned that games designed for constant button mashing don't work as well when every button press require a massive arm movement.

I'm pretty sure I threw this in the trash soon after my first play session, which is kind of a shame, because eBay sellers are apparently asking $90 for units in "very good" condition. Believe me, that selling price would have been the only real value I got out of the purchase.

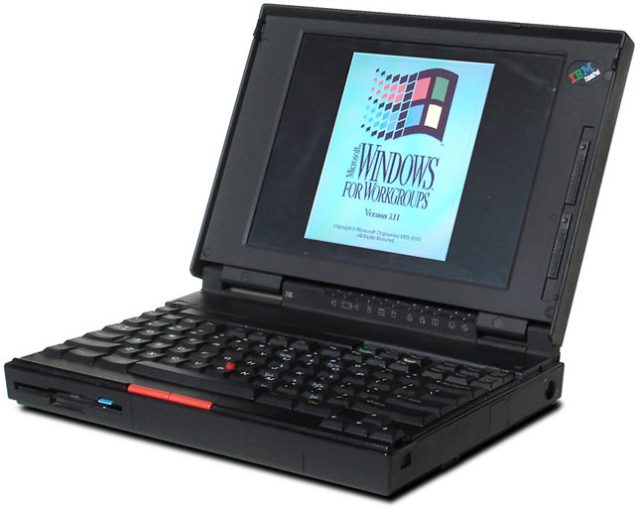

IBM Thinkpad, by Matthew Lasar

In the mid-1990s I purchased an IBM Thinkpad. Everyone was raving about them (and lots of folks rave about them still). But for whatever reason, mine was just about the worst laptop computer that I have ever owned.

How did it fail? Let me count the ways. Software would not install on the Windows-powered machine. I still have 3.5 inch disk laden recollections of repeatedly trying to get MS Word to load up on the device, with mysterious failure messages that drove me nuts. When, mysteriously yet again, the software did finally install, my larger files endlessly crashed, the OS complaining about insufficient memory.

Although my contract claimed to include technical support via a telephone number, the gentleman philosopher with whom I spoke was apparently paid not to assist me with this problem, but to offer me condolences. "It might be the hardware," he pontificated. "It might be the software."

"Then again, perhaps the atmosphere is to blame," I snapped, before hanging up the phone.

This was only the beginning. The modem failed, so I took it over to that most hazardous of places: a computer warranty repair depot. That shop was owned by, alas, Computer City, soon to be acquired by CompUSA. Three weeks later I picked up the machine. The modem worked fine; unfortunately, the printer and external speaker no longer functioned.

I thought of bringing the clunker back, but by 1998 the chain's new owner had shuttered around 50 Computer City stores, including the one I dealt with. It was time, I concluded, to move on to my next big hardware adventure.

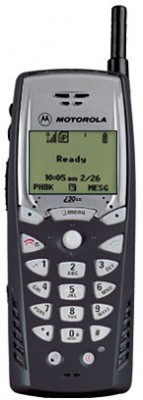

Nextel i30sx, by Casey Johnston

It's safe to say now that Nextel, as a network, had virtually no redeeming qualities from the start, which is why it doesn't exist anymore. But one of its most repulsive aspects was its handset offerings. Due to circumstances beyond my control, in 2004 (t-minus three years to the iPhone), I was blessed with a cell phone that was actually technically incapable of sending a text message: the Nextel i30sx.

Up until I was 16, I did not have a cell phone. I wasn't really hankering for one, even as my friends graduated from playing Centipede on their Nokia candy-bar phones to taking the earliest cell phone pictures (sexting, fortunately, had yet to be invented by our younger brothers and sisters). In the fall of junior year, my parents gave me an i30sx. I was repulsed by its design: hideous and thick, with rubbery keys, a telescoping antenna, and monochrome screen.

To be perfectly hipster-y about it, text messaging was not yet A Thing in 2004. But I had general phone conversation anxiety, so text was (and is) an ideal medium of expression. To my dismay, unlike every other cell phone in I saw in my peers' hands, the i30sx could not send text messages. Weirdly, though, it could receive them. I couldn't quite believe my own memory that this was the case, but the phone's manual (PDF) proves it to be true—some committee design team actually thought one-way messaging was a completely practical feature.

I did work out a system where I could text friends' phones from AIM, and they would respond to my Nextel phone number, but that was too inflexible. A few months later, I hauled off to the AT&T store and bought a Sony Ericsson pay-as-you-go phone with my hard-earned, grocery-store-checkout dollars. At long last, I could send all the text messages I wanted—for 10 cents a pop.

reader comments

363