SAN FRANCISCO—Two of the world's most powerful tech CEOs—Oracle's Larry Ellison and Google's Larry Page—testified in the same San Francisco courtroom today, presenting very different portraits of Google's behavior while building its Android operating system.

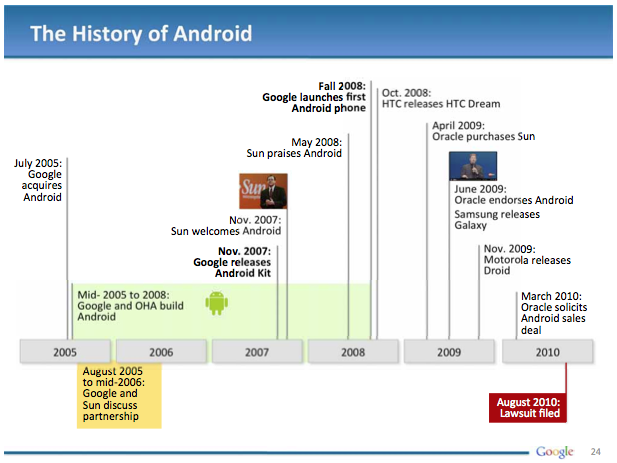

The all-star day of testimony was the second day of trial in Oracle v. Google, a lawsuit about whether Google violated copyright and patent rights that Oracle acquired when it purchased Sun Microsystems in 2009.

Google's opening: "The Java language is free and open"

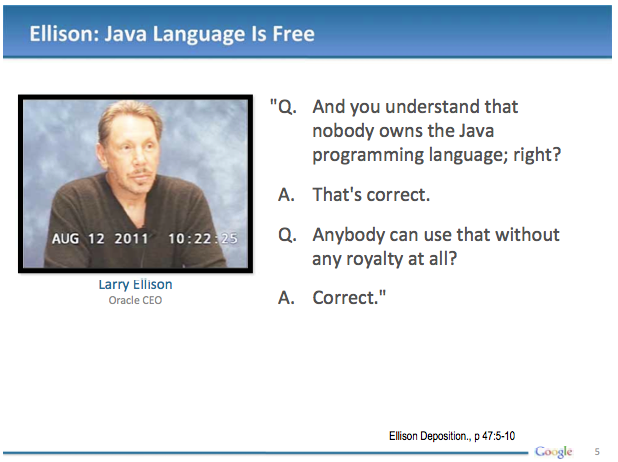

Oracle's argument is that while Java is an open-source language free to all, using the APIs as Google did requires a license—and the fact that Google doesn't have one puts them on the wrong side of copyright law.

Today Google responded to that argument, as its lead lawyer, Robert Van Nest, gave a one-hour opening statement to the jury this morning. The Java APIs are free for all to use, just like the Java language itself, Van Nest told the jury—and Google built Android on its own, from scratch. When it was finished, Java's creator, Sun Microsystems, wasn't angry. It didn't come demanding royalty payments. In fact, Sun CEO Jonathan Schwartz congratulated Google publicly and welcomed Android.

"The Java language is free and open; it's been in the public domain for years," Van Nest said. "And those APIs you heard about, they are necessary just to use the language. Without the APIs, the language is basically useless."

Building Android took three years and thousands of engineering hours. It was built from the ground up, Van Nest said, not by copying Sun or anyone else. After months of combing through the 15 million lines of source code that make up Android, Oracle lawyers have found exactly nine lines of code that are the same as Sun's code, Van Nest said. And, he promised, the jury will get an explanation about even those nine lines. "They were originally written when [a Google engineer] worked at Sun. He made a mistake, and those nine lines of code shouldn't have been in there."

As for the damning e-mails shown by Oracle's lawyers the day before—the ones where Google execs and engineers talked about their need for a Sun license—those were misleading. They were part of an extended negotiation between Sun and Google that ultimately didn't pan out, Van Nest said. When Google was strategizing about Android, it considered bringing on Sun as a partner but ultimately decided not to. Sun recognized Google's right to build Android using Java on its own. Android "has strapped a set of rockets to the Java community," Sun CEO Schwartz wrote in a congratulatory blog post back in 2007, which was shown to the jury today. "We welcome Android to the Java community."

The real story, Van Nest said, was that Oracle had tried, but failed, to get into the smartphone market itself. Oracle had a secret project called "Java Phone," to build a smartphone OS using Java. It never got past the research stage. It was Google who had succeeded, beyond anyone's expectations. So now? "They [Oracle] want to share in Android's profits, without having done a thing to create that profit," said Van Nest.

Larry Ellison on the stand: "The only company that hasn't taken any license... is Google."

Larry Ellison was called as Oracle's first witness not long after the opening statement. Wearing a gray suit and purplish tie, Ellison walked casually to the witness stand and was sworn in. He was smooth and calm as his lawyer, David Boies, walked him through Oracle's story about the Java acquisition.

Oracle today has more than 100,000 employees, Ellison testified, and spends upwards of $5 billion on research and development. Nearly all of that goes towards creating new software.

"Would it be possible without copyright protection?" asked Boies.

"Well, no," said Ellison. "If people could copy our software—create cheap knockoffs of our products—we wouldn't be able to pay for our engineering."

At times Ellison came off more like a technical witness than a CEO, explaining to the jury how APIs worked or the structure of Java. He emphasized the value of both the design and the content of Oracle's programs. These are key points considering Oracle is making a copyright claim against Android despite the fact it has only a small sliver of copied code to show.

Ellison's testimony stressed that the APIs Oracle wants licensing money for are no small thing. Creating APIs "is arguably one of the most difficult things we do at Oracle," said Ellison. "It's done by our most senior and talented software engineers."

Even though Java code was published openly, every company that used Java APIs needed to take some kind of license for it. (One of the licenses available was the free GNU Public License, although Ellison said that even a company using Java under the GPL would have to run, and pay for, a compatibility test called the TCK.)

“The only company I know that hasn’t taken any of these licenses is Google,” said Ellison.

During cross-examination, Van Nest emphasized Oracle's aborted attempt to get into the smartphone business, asking about a confidential plan Oracle code-named "Java Phone." E-mails showed, and Ellison acknowledged, that Oracle was eager to negotiate with Android manufacturers. The company even considered buying both Palm and RIM. (Ellison ultimately decided that Palm's technology wasn't competitive, and RIM was too expensive.)

Ellison downplayed the documents Van Nest displayed to the jury, dismissing them as brainstorming that didn't go anywhere. "I had the idea, we explored the idea--and I decided it would be a bad idea," he said.

Larry Page on the stand: "I don't think we did anything wrong."

After Ellison's testimony, Oracle vice-president Thomas Kunian testified about the company's licensing practices for a bit more than an hour.

With just 20 minutes left before the end of the trial day came at 1:00 pm, Oracle lawyers called Google CEO Larry Page as their next witness. (Judge William Alsup, who has a reputation as a workhorse, is keeping the Oracle-Google dispute to a strict 7:30 am to 1:00 pm schedule each day, hearing his criminal cases in the afternoon.)

Page had been waiting in the hallway outside the courtroom, trailed discreetly by a beefy security guy. He emerged from a meeting room down the hall, and was quickly joined by a coterie of lawyers before the group huddled in an alcove next to the courtroom. The group laughed in hushed tones as Page joked about something. The court security officer indicated it was time to go in, and they did, followed by a few reporters re-entering the court.

In court, Page's demeanor was strange, almost overly focused. Someone had clearly prepped him by telling him to smile, and make eye contact with the jury. He certainly did both. In fact, he never stopped. The constant smiling and staring made him look somewhat maniacal at times. As David Boies grilled him about the creation of Android, Page answered his most of his questions without even glancing in his direction. Boies started off by focusing on the "clean room" approach Google had used in building Android.

"You understand a 'clean room' would be a project that had people in it who did not use, reference, or know, the intellectual property of someone else?"

"It's a process used to develop software where you carefully control the information you use to do that," replied Page.

"So you understood that you might be able to use something that was publicly available in a clean room," said Boies. "But you could not use somebody else's copyrighted material, and could not use developers who referenced or knew someone else's copyrighted material, right?"

"I don't think we did anything wrong," during the process, said Page. He acknowledged he didn't know all the details of the clean room work for Android, and didn't supervise it himself.

Boies kept asking about the 'clean room' until Alsup actually cut off his questioning, telling him he was getting too close to dictating the details of copyright law himself (which is the judge's role). "Be mindful that there are [legal] decisions on reverse engineering and fair use," said Alsup. "You're getting very close to getting into issues of law." Boies thanked the judge but continued with the 'clean room' questions.

"Within the software industry, is there a recognized understanding of what a 'clean room' is?" asked Boies.

"Well, yeah," said Page. "And I have no reason to think we did anything that was not in accordance with that."

"If you discovered Android had lines of code that were literally copied—would that be a violation of Google's policy?"

"That seems like a hypothetical question," said Page. "But in general, yeah, we would take that seriously."

Shortly after that, Alsup cut Boies off. "This is getting argumentative," said Alsup. "It's best to move on to something else. You made your point."

Boies wrapped up the day just a few minutes after that line of questioning was shut down. Page will be back on the witness stand tomorrow morning.

Listing image by Image courtesy of Oracle

reader comments

130