Alexa Is a Revelation for the Blind

Legally blind since age 18, my father missed out on the first digital revolution.

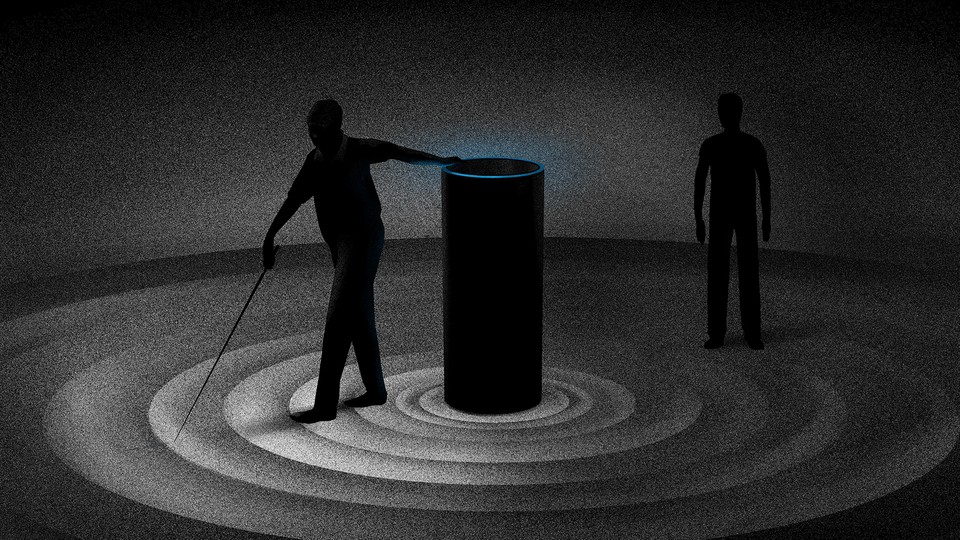

“Is it ‘Electra?’” my father asks, leaning in close to the Amazon Echo my mother has just installed. Leaning in close is his trademark maneuver: Dad has been legally blind since age 18, the result of a horrible car crash in 1954. He has lived, mostly successfully, with limited vision for the 64 years since.

“Call it the right name!” my mom shouts as Dad tries to get the device’s attention. In response, he adopts an awkward familiarity, nicknaming the Echo “Lexi.” Hearing this, I groan. There goes Dad again, trying to be clever, getting it wrong, and relishing the ensuing chaos.

Then I stop myself. Isn’t it possible that he expects Alexa to recognize a prompt that’s close enough? A person certainly would. Perhaps Dad isn’t being obstreperous. Maybe he doesn’t know how to interact with a machine pretending to be human—especially after he missed the evolution of personal computing because of his disability. Watching him try to use the Echo made me realize just how much technology forms the basis of contemporary life—and how thoroughly Dad had been sidelined from it.

Companies like Amazon are presenting voice-activated devices as the ultimate easy-to-use technology. Just speak naturally to Alexa (or Apple’s Siri, or Google’s Assistant), and it will answer your questions and respond to your commands. What could be simpler?

But every other supposedly obvious technical interface has proved to require some prior knowledge or familiarity. People had to be trained to operate a mouse, for example; direct control of a cursor was awkward until it became habitual. The touch screen built on the mouse, replacing the pointer with the finger. Its accompanying gestures—flicking through a feed or pinch-zooming a map or swiping right on a love interest—have come to feel like second nature. But none of them are actually natural.

Voice assistants appear to bypass that legacy, offering hands-free operation for able-bodied folk and new accessibility for those with limited mobility or dexterity. Yet they still require expertise. Dad loves classical music, so I suggest that he try out Amazon’s extensive music library. “Alexa, play Brahms’s ‘Hungarian Rhapsody No. 5,’ ” he says. He’s gotten it partly wrong—the composer is Liszt, not Brahms—but Alexa throws up her hands completely: “I can’t find ‘Rhapsody No. 5’ by Brahms Hungarian.” Someone familiar with web searches would realize he’d provided too much information and simplify the request. Instead, Dad just looks baffled.

Another problem: While voice-activated devices do understand natural language pretty well, the way most of us speak has been shaped by the syntax of digital searches. Dad’s speech hasn’t. He talks in an old-fashioned manner—one now dotted with the staccato march of time. “Alexa, tell us the origin and, uh, well, the significance, I suppose, of Christmas,” for example.

Dad always hid his disability as much as possible, seeking to pass as able-bodied. This worked well enough—he completed a doctoral degree and maintained a private practice as a clinical psychologist for decades—until, one day, it didn’t anymore.

The issue was partly his age, and partly the way the media ecosystem had changed. Print newspapers, television, and radio had lost ground, and information got siphoned into glass-and-metal rectangles that require clear vision and deft motor control. Dad can read newspapers with a strong magnifier and watch television if he sits close enough to the set, but those formats don’t require user interaction like computers do. Print doesn’t require scrolling or zooming, and its pages don’t time out and turn themselves off.

A screen reader—a kind of software that provides assistance for people with vision problems—might have made computers more accessible to Dad, but arthritis hindered his fine-motor movement, and obstinacy made him spurn help of any kind. “I can see it,” he often says, ironically. Computers and smartphones seemed like unnecessary accessories at first, ones he could ignore while remaining operational in the world. But those devices have become ever more central to daily life. Sure, Dad can still pick up the phone and call people. But who talks on the phone anymore?

Now, at 82—and with a different technology on offer—Dad is willing to adapt. After his initial fumbles with the Echo, he begins to get the hang of it, asking Alexa for football scores and stock-market updates, or to tell him who the president of Venezuela is. He discovers that, for some reason, Alexa isn’t set up to report the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Nikkei index, and he begins to enjoy posing questions the device can’t answer. He taunts it the way everyone else does: “Alexa, what would you like for breakfast?”

Dad’s background as a psychologist makes his initial error of address—Electra rather than Alexa—accidentally funny. Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, coined the Electra complex to name a girl’s competition with her mother for the attention of her father—the feminine corollary of the Oedipus complex. But unlike in Jung’s formulation, my mother relishes this new interloper. For decades, Mom has facilitated my father’s access to news and information—and she’s happy to be unseated by a rival, even if it’s just a fabric-covered cylinder with a light on top. Even so, this new setup is not perfect. “Dad often gets his commands wrong,” Mom reports, “and he gets frustrated when she does not understand him.”

When I was younger, Dad would write me letters—big, weird, angular script on stationery left over from his private practice. That became harder for him over time, as his vision and dexterity degraded—and I was never a very good written correspondent anyway. Then email and text messaging came along, and communication began to channel through computers—and for Dad, through my mother. There’s a difference between being read a letter addressed to you, and being a secondary party to communications on someone else’s personal device.

The Echo promised to rectify this slight. Dad can dictate a message to Alexa, and it will arrive on my Echo, as well as in an app on my phone, as both a recording and a transcribed text message.

At first, Alexa resists: It has a hard time understanding “Ian” and matching my name in Mom’s address book. (And the fact that it’s “Mom’s address book” only demotes Dad to the dependent invalid he so hates to be.) After we iron this out, Dad and I start using the Echo for small talk—quick life updates, holiday greetings, sports commiserations.

The recordings Alexa delivers to me are comprehensible, but Dad’s mumbles and pauses make the transcriptions incomplete or inaccurate. This mode of communication feels like something between leaving voicemails and texting, a technological pidgin that travels across eras in time as much as it does across the space between my father and me. Still, we probably haven’t spoken this often in years, if this counts as speaking.

Then, while out to dinner with their neighbor Ron, my parents discover that he recently bought an Echo—making Ron another Alexa pen pal for Dad. Soon after, I ask Dad how his correspondence is going. A pause follows. Dad’s hearing is on the wane, too, and he takes a medication that makes him drowsy, so sometimes he vanishes silently from a conversation. At last, he reports: “It’s nice to be able to communicate back and forth.”

I let the idea roll around in my head and realize what I’ve gotten wrong. I was thinking of the Echo as a tool for exchanging information. That explains why I’m sometimes frustrated with the results. But for Dad, the Echo doesn’t carry information so much as it facilitates independence of connection—to me, to Ron, to the fast-moving facts and responses that smartphone and Google users have had at their fingertips for years, or decades.

It doesn’t really matter whether Alexa provides Dad with useful knowledge or a seamless way to communicate. It does something more fundamental: It allows him to connect with people and ideas in a contemporary way. To live fully means more than sensing with the eyes and ears—it also means engaging with the technologies of the moment, and seeing the world through the triumphs and failures they uniquely offer.

This article appears in the May 2018 print edition with the headline “What Alexa Taught My Father.”