In Washington, D.C., where I live, finding my way around is typically as simple as mapping my route from one address to another. Elsewhere in the world, however, things aren’t always quite so simple, especially in outlying or undermapped locales, where roads may not have consistent names and fixed addresses are sometimes few and far between.

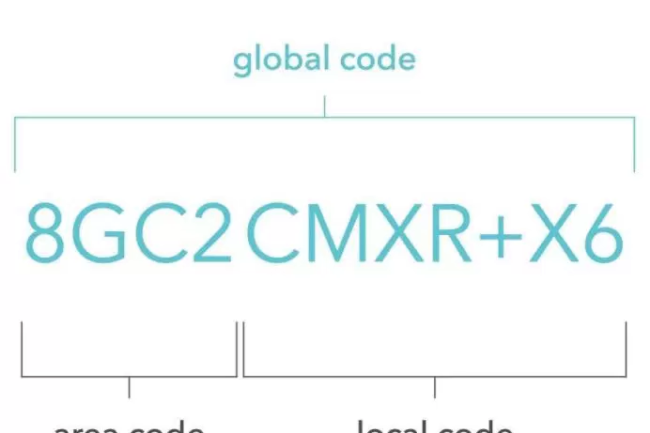

In an attempt to solve some of these problems, Google has introduced a new global addressing system this week that it calls Plus Codes. As the company’s Indian division explained in a blog post Tuesday, “This system is based on dividing the geographical surface of the Earth into tiny ‘tiled areas’, attributing a unique code to each of them.” Those tiles combine a six character “local code” (e.g. CMXR+X6) that describes a 14 meter–by–14 meter square with a broader four character “area code” that covers a 100 kilometer–by–100 kilometer square (e.g. 8GC2). As the company explains elsewhere, it can also generate codes with an even greater degree of specificity, further dividing the earth up into 3 meter–by–3 meter units.

Google isn’t the first company to attempt such a rethinking of cartographic divisions. In 2016, Slate’s Joshua Keating described a similar project from a British startup called What3Words that similarly sectioned the earth up into 57 trillion 3 meter–by–3 meter squares. Instead of complex alphanumeric codes, What3Words assigns these locations three word names such as basis.laws.slice.

The What3Words approach has a clear advantage over Google’s, since even the randomest combinations of words are likely easier to recall than more abstract sequences of numbers and letters, whether or not those codes are, as Google promises, similar for “[p]laces that are close to each other.” Where phone numbers, for example, are simple enough to remember, the addition of letters could clearly lead to misdirection, especially if you’re trying to provide a location over the phone. Indeed, Google’s system seems optimized for machines rather than humans, much as the modern internet already is.

Nevertheless, on this front, it’s easy enough to imagine applications of Google’s system that would improve the interface between human users and emerging technologies. Drone delivery, for example, may ultimately help route much-needed goods to out-of-the-way destinations, but directing autonomous aircraft might be difficult in some areas. While precise GPS coordinates may be easy for a robot to find in some circumstances, they’re also impractical reference points for humans filling out order forms and may not offer ideal drop-off zones. Location codes could provide a happy medium, since they should be easier to write out and may be more accessible for the craft. In other words, the codes could provide a more human-friendly way of interfacing with otherwise-alienating algorithmic calculations.

Though more consistent addressing systems—especially in rural regions—are likely a good thing in other ways as well, there are reasons for caution here. Google’s blog post notes, “all that’s needed [to use the codes] is Google Maps on a smartphone.” For now, at least, this means those using the system are at least partially shackled to Google’s own app infrastructure. While that’s likely fine for ordinary civilian uses of the system, it may limit other applications.

Consider one of the most compelling proposed practical scenarios for the proposed system: “guiding emergency services to afflicted locations.” If there’s a car accident on a remote road with no nearby addresses and few definite landmarks, the codes could make it easier to dispatch ambulances and other relief vehicles. To do so, however, first responders would also have to employ the same Google-based systems. In effect, that would require municipal authorities to get on board with a privately owned and operated system, potentially leading to a de facto embrace of a single company’s technology.

Google may address such concerns in time. As it explains, the Plus Codes system is open-source and free. It also claims that the codes will be usable offline and “can be printed as a grid on paper, posters, and signs.” Still, its uptake will ultimately depend on our own willingness to reconfigure our own mental maps, committing to a system that has more to do with computerized thinking than our predigital ways of moving through the world.