Winter is coming—and not in that Game of Thrones sense. Many people are starting to button up across the US, but while you might have to turn the heater up too, there’s reason to stop and think before blasting the warm air. Like so many of the best aspects of modern living, heaters aren’t necessarily great for the environment. In fact, your heating habit may be bloating your carbon footprint dramatically.

With the Trump administration ditching the Paris Climate Agreement, of course, there may be no federal mandate for individuals and organizations to shrink their carbon footprint. But many people—for reasons ranging from the financial to the environmental—still want to find out how to shrink their impact on the Earth. While it’s hard, there is a way.

Carbon footprints are essentially a convenient way for scientists and environmental advocates to provide you with a number—typically in tons—of the C02 emissions you produce each year. Calculated based on a number of factors including where you live, what you eat, and how you get around, the size of each person’s C02 footprint varies widely. Things are especially different between city slickers and suburbanites, as urban living lowers carbon emissions by 20 percent. Still, the average American clocks in at 16.4 metric tons, or some 36,00 pounds, of carbon dioxide and its greenhouse gas equivalents each year, according to the World Bank. That made for a shared national footprint of about 5,300 million metric tons in 2015, which continues to contribute to the acceleration of global climate change.

These stats, alarming to many, have generated debate about how to reduce our individual footprints, thus reducing our country’s. Some find themselves wondering what can be done to shrink—or even eliminate—their carbon footprint. While it's difficult, new and improved technologies mean the shrinkage potential is getting a lot bigger (and, perhaps, a little simpler) every day.

You are what you meat

One of the biggest contributors to an outsized carbon footprint is hiding in your diet. To the untrained eye, a T-bone steak may not look like a veritable oil well, but it turns out to be exactly that. Beef generates so many greenhouse gas emissions, from carbon dioxide to the even more powerful methane, that some scientists have argued Americans need to prioritize cutting beef over cutting cars.

Cows, it turns out, are particularly inefficient growers. Producing one pound of beef in the United States requires up to 661 pounds of dry food like grain. (Pigs and poultry, meanwhile, require about one-fifth this much feed per pound of meat.). And this grain isn't easy to produce; it requires immense amounts of land (if you count cropland and pastures, some 40 percent of the United States’s total territory), thousands of gallons of water, and synthetic fertilizers to reach its full potential, not to mention gas-guzzling transportation to the feedlot. Not only that, but cows are also notoriously gassy, releasing a bit of methane with every toot.

These problems are made all the more troubling due to the sheer amount of beef we eat. Between 2005 and 2014, beef consumption in United States sat steadily at about 24 billion pounds a year, according to the US Department of Agriculture. That's about 50 pounds of beef for every American. More alarming still, developing nations like China are only just beginning their foray into beef eating. Between 2012 and 2016, China’s per capita beef intake increased 33 percent, from about nine pounds per person five years ago to about 12 pounds today. And that number is likely rising.

A 2014 study of diets in the United Kingdom showed just how much difference dietary decisions can make. The researchers calculated the carbon footprint of carnivores as compared to vegetarians and vegans. Those who consumed a “high meat diet,” defined as just 100 grams (3.5 ounces) of meat, generated seven kilograms (15.8 pounds) of food-related carbon a day, which is the equivalent of running an average car for 17.5 miles. That’s huge, especially when you realize 3.5 ounces is smaller than a standard burger patty. Vegetarians, meanwhile, hit a daily average of about 3.8kg (8.4 pounds) of food-based carbon.

Naturally, the cow’s number one byproduct—dairy—is also a major producer of carbon. To produce one gallon of milk requires about eight kilograms (17.6 pounds) of carbon, according to a presentation by L.E. Chase, a dairy researcher at Cornell University. A report co-sponsored by the USDA suggested producing hard cheese resulted in roughly 0.5 pounds of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) gases per pound of cheese. That’s part of the reason why the same 2014 dietary study found that vegans—who, like vegetarians, eschew meat, but also avoid eggs, dairy and other animal byproducts—produced just 2.9kg (6.3 pounds) of food-related carbon each day, or two pounds less than vegetarians.

The sci-fi solution

Now, meat-eaters don’t need to give up these foods entirely to reduce their carbon footprints. In fact, a scientific solution may allow them to barely alter their dietary habits in the near future.

Back in 2012, scientists announced they'd been cooking up lab-grown meat, which would be a more exciting development if not for the $330,000 price tag. To grow it, the researchers took cells out of beef cattle and fed those cells water, vitamins, minerals, protein, antibiotics, and sugar. It technically worked—meat was made—and slabs of meat have since popped up in petri dishes around the world.

But even if “cultivated meat” were widely-available and affordable, it’s not clear how much better these burgers would be for the ol’ carbon footprint. In 2011, the journal Environmental Science & Technology published an analysis that suggested lab-grown meat would emit 96 percent less pollution than traditional beef. But a 2015 study in the same journal questioned those conclusions, arguing that while less land and grain will be needed, large-scale bioengineering could have its own negative consequences, namely due to the energy required to nourish and grow the cells.

Today, lab burgers aren’t the only meaty alternative to traditional beef. Several start-ups are analyzing the molecular profile of beef and replicating it using plant compounds. Last year, NPR grabbed a bite, claiming Impossible Food’s “bloody plant burger smells, tastes, and sizzles like meat.” Still, it’s environmental benefits are unclear and the FDA just announced it wants more data on the safety of soybean leghemoglobin, a key ingredient in the “impossible burger.” So for now, conscious dietary decisions remain the primary way to reduce your carbon footprint through food.

How to hitch your wagon

Unless you own a fully electric vehicle, every time you turn your key in the ignition on your car, you’re burning fossil fuels. While planes, trains, and cargo ships are a factor, our cars are the main reason why transportation accounted for 27 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions in the United States in 2015.

Fortunately, solutions are abundant—at least if you live in a city.

Data from 2016 suggests that the per passenger mile of carbon from a single occupancy vehicle is about 411 grams (0.90 pounds). This compares to an average 0.22 pounds per passenger mile for heavy rail transit like the subway or vanpools, per the Department of Transportation’s 2010 data. That same data also shows that buses coming in at 290 grams (0.64 pounds) per passenger mile, light rail like Boston’s Green Line at 163g (0.36 lbs), and commuter rail like Caltrain at 150 grams (0.33 lbs). No matter what stats you’re looking at, they all agree that any public transit solution is better than a car if you want to reduce your carbon footprint. The issue, of course, is access to good alternatives are dependent on where you live.

This makes Uber, Lyft and other companies that offer a ridesharing service a potentially important consideration (their regular service is no different from any other car ride). Uber has long touted an eco-conscious business model, proposing the rideshare scheme ultimately gets cars off the road. But, much like meatless meat, this model may not be as great as its proponents say. Little publicly-available data actually demonstrates the promised emissions reduction from the modern rideshare economy is real. Some research indicates these apps aren’t just reducing the amount Americans drive their cars—they may be cutting the trips people take by public transit, too.

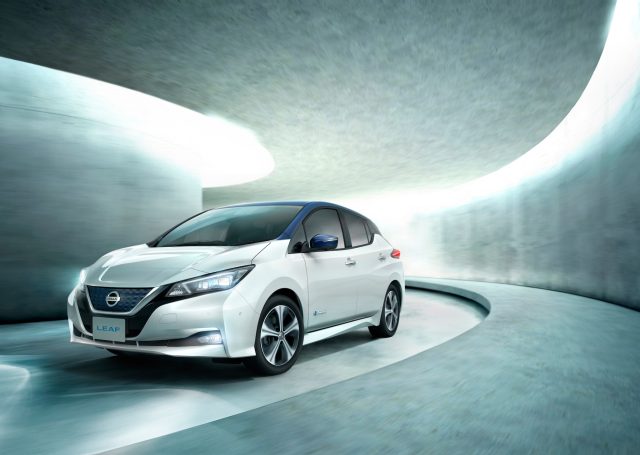

Sometimes, though, having your own car is strictly necessary. In situations like these, choosing an eco-friendly car is the key to shrinking your footprint. Right now, there are two classes of eco-friendly cars: electric and energy efficient. Electric cars are powered by a high-power battery, typically charged overnight through an outlet or at a special EV charging station. All-electric vehicles include the Tesla, Nissan Leaf, and Chevy Bolt. Energy-efficient cars, meanwhile, are cars run on gas, but are designed to travel more miles per gallon. These include hybrid gas-electric vehicles like the Prius and even extremely light cars like those made by Fiat. And plug-in hybrids offer some of the best features of both.

Right now, if you have the choice, an electric vehicle is better than an energy-efficient vehicle if your goal is to lower your carbon footprint. Electric vehicles have greenhouse gas emissions similar to a car that gets 68 miles to the gallon, according to 2015 research from the Union of Concerned Scientists. That's a gas mileage that basically doesn’t exist for non-electric vehicles.

Still, there are some downsides to trading in your latest model for an EV. For starters, most people probably can’t afford a new car just because it may be more environmentally friendly. And, paradoxically, building any new car—even an efficient one—actually produces a lot of emissions. The numbers are hard to nail down and depend on the model, but building a new car can require anywhere from six to 35 metric tonnes (10,000 to 75,000 pounds) of carbon to build and ship, according to author Mike Berners-Lee’s The Carbon Footprint of Everything.

When a new car is not an option, lowering emissions means finding ways to drive your existing car less and, when you do drive, driving differently. Keeping a vehicle light and its tires filled with air improves its range. Driving steadily, avoiding hard acceleration or deceleration, and maintaining the optimum speed for your vehicle (typically around 50 miles an hour) can also earn you a spot in the “hypermiling” club of motorists looking to milk every last mile out of a gallon.

A new take on an old solution might work even better, for those who are physically able. The electric bike combines body power with a simple battery. With such a machine, even newbies can reach speeds of 20 miles per hour and power through long or steep trips that might otherwise tucker a casual biker out, making it a good alternative for people with long commutes. And even with the support of the battery, electric bikes have proven to be good for the environment and for your health.

The sci-fi solution

If none of these changes are radical enough, there may be a futuristic fix to America's transportation problem lined up. As Ars readers may expect, this plan comes courtesy of Elon Musk.

The Hyperloop, which Musk dreamed up and now intends to build between New York City and Washington, DC, will supposedly move people and cargo at 600 miles an hour, using a combination of natural propulsion and (hopefully green) electricity. If that sounds like it might cut down on travel times and carbon emissions, that’s because those are two of Musk’s most important goals for the project. Still, a Hyperloop that really goes the distance is likely decades off, given the current state of the technology—and the incredible regulations involved.

Assuming you can’t stay frozen in place, the most environmentally-friendly transportation strategy today will rely on a healthy mix of walking, biking and public transportation, with electric cars used in a pinch.

reader comments

326