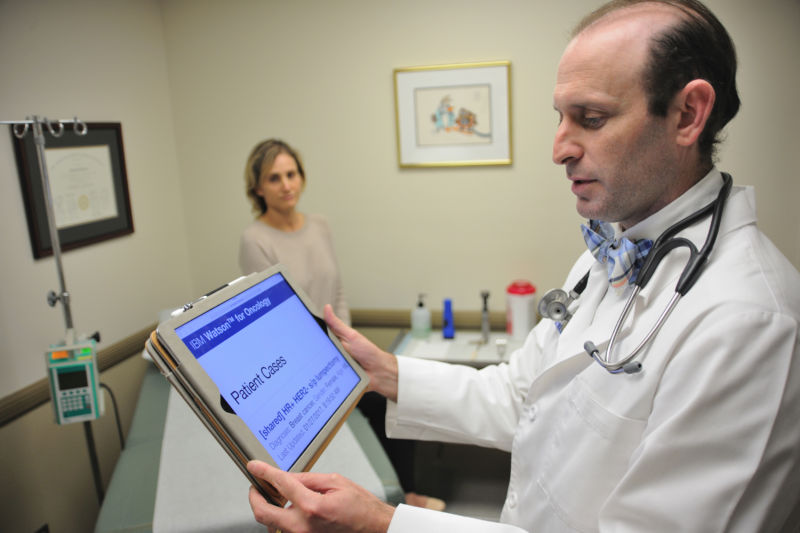

IBM’s Watson is on the move. With the new ability to quickly develop clever personalized treatment strategies for cancer patients, Watson is making its debut in hospitals around the world—from the US to India, Korea, and China. Earlier this month, a medical center in Jupiter, Florida, announced it too was welcoming the famed, Jeopardy-winning computing system into its hospital rooms.

But, there’s one place where Watson isn’t moving: The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. In fact, Watson is frozen there. And it’s more than just a computer glitch.

According to a blistering audit by the University of Texas System, the cancer center grossly mismanaged its splashy program with IBM, which started back in 2012. The program aimed to teach Watson how to treat cancer patients and match them to clinical trials. Watson initially met goals and impressed center doctors, but the project hit the rocks as MD Anderson officials snubbed their own IT experts, mishandled about $62 million in funding, and failed to follow basic procedures for overseeing contracts and invoices, the audit concludes.

IBM pulled support for the project back in September of last year. Watson is currently prohibited from being used on patients there, and the fate of MD Anderson’s partnership with IBM is in question. MD Anderson is now seeking bids from other contractors who might take IBM’s place.

Meanwhile, a similar project that IBM started with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York around the same time frame has already wrapped up. It resulted in a commercial product that is currently making its way into hospitals around the world, including in Jupiter.

“I am incredibly excited about where we are at this point in our history,” Rob Merkel, vice president of Oncology and Genomics at IBM Watson Health, told Ars. IBM is working on several projects to get Watson helping with clinical trials, cancer patients, and genomics. “I think it’s really important that you read the [UT audit report] and keep that in mind,” he said. But in terms of the broader look of Watson’s oncology work, “I’m very, very excited.”

So what went wrong at MD Anderson?

First, the cancer center isn’t new to controversy. The center’s president, Dr. Ronald DePinho, and his wife, Dr. Lynda Chin, have been in the middle of several scandals since they both joined the cancer center in 2011. Before moving to Ars, Eric Berger reported extensively on the scandals for The Houston Chronicle, along with his colleague at the newspaper, Todd Ackerman. DePinho drew criticism for his ties to drug companies and hyping therapies, among other things.

Chin, who was formerly the head of MD Anderson’s department of genomic medicine and co-director of its Institute for Applied Cancer Science, has been repeatedly accused of benefitting from favoritism. She was involved with a controversial $20 million incubator grant awarded by a state cancer agency in 2012 without scientific review. The grant was rescinded after it sparked wide-spread controversy, plus high-profile resignations. State lawmakers even wrote legislation to overhaul the granting agency following the fiasco. Then in 2013, Chin drew fire for a lavish office renovation, which some estimated to cost around $2 million at a time when budgets were tight.

Chin left the position in 2015 to become an associate vice-chancellor in the University of Texas system. But, before she left, she was personally in charge of the Watson project.

According to the audit, Chin set up contracts and service agreements with IBM and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), which was supposed to develop a business plan for any Watson-based oncology products MD Anderson created. However, most of the agreements weren’t procured through competitive processes, some weren’t formally justified or approved, and some weren’t properly authorized, the audit found.

Nevertheless, by September 2016, MD Anderson had paid out around $39 million to IBM and nearly $23 million to PwC.

As the partnership progressed, Chin also didn’t get the Watson program approved through MD Anderson’s Information Technology’s development policies and processes. Chin aggressively argued that the Watson project was a research project, not an IT project. However, the project relied on IT professionals.

Glitches of the human kind

Though there’s ambiguity in MD Anderson’s rules on IT involvement, the auditors concluded that the IT department should have been overseeing the work. In fact, they hinted that integration of Watson with the hospital’s software was a sticking point for progress—something IT leaders would have been in a good position to help address.

In their report, the auditors noted that:

“Medical oncology staff also told us that internal pilot testing of [Watson’s work with lung cancer treatment] achieved an accuracy of prediction near 90 percent, but advised that significant updating is needed before [Watson] can be tested further. We were told that [Watson] must be integrated to the current medical records system and drug protocol and clinical trial data must be updated before internal pilot testing can resume…”

That is, the hospital had updated the software it was using for electronic medical records. But the new software wasn't compatible with how Watson was configured and project leaders failed to perform updates that would have allowed the systems to play nicely. This kept Watson from being fed new information. Without up-to-the-minute updates on a patient’s health records, new medical studies, and drug data, Watson simply can’t come up with the best treatment options.

In a fiery response, Chin accused the auditors of trying to undermine her authority by disagreeing with her decision not to follow standard IT policies. She also argued that because IT leadership didn’t specifically request that she follow their policies, they were silently agreeing with her decision.

She concluded:

“Your dismissal without justification of my expert opinions in my role as the [principal investigator] who conceptualized, designed and led the project, coupled with your disregard of the obvious interpretation as inferred by the actions of the IT leadership as noted above, calls into question the objectivity of your findings.”

Lastly, auditors found that invoices were paid regardless of whether services were provided, but weren’t consistently paid or paid in a timely way. Some fees were suspiciously set at rates just below the amounts that would trigger review and require approval by the Board of Regents. And, MD Anderson paid out money from donations that hadn’t actually come through yet—leaving the project with an $11.59 million deficit.

After several stalls, IBM walked away from the project in September 2016.

In a statement to Ars, MD Anderson said:

“When it was appropriate to do so, the project was placed on hold. As a public institution, we decided to go out to the marketplace for competitive bids to see where the industry has progressed… MD Anderson remains committed to exploring how digital solutions can accelerate the translation of research into advanced cancer care for patients.”

Editor's Note: The post has been updated to provide more information on Watson's compatiblity with MD Anderson's medical record software.

reader comments

170