October 21, 2016 will go down as one of the biggest cyber-attacks in the history of the Internet – perhaps the biggest ever. We’re going to learn a lot from this one, and we need to be sure to take steps to avoid it happening again.

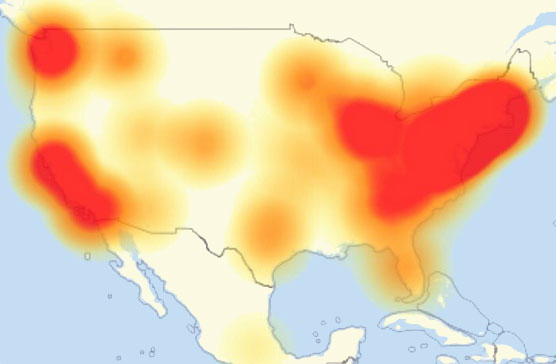

DDoS attack map from Breaking 911 Weather at 3:24 p.m. on October 21, 2016.

What Happened

What happened is that a huge distributed denial-of-service (DDOS) attack began at about 7:10 a.m. EDT that impacted every service and every device using Dyn as their domain name server. It impacted Level 3 Communications, Amazon, Twitter, Reddit, Spotify, PayPal, Netflix, The New York Times, Wired, Charter, Comcast, Verizon, AT&T, PlayStation Network, Cox, and many other domains.

The initial attack was resolved after about two hours, but it was followed by a second attack early Friday afternoon, and a third wave was reported to have begun around 4:30 p.m. EDT.

How the Attack Spread

There’s a class of hackers that loves nothing more than finding security flaws in operating systems, sharing that information with whoever is responsible for it (Apple, Microsoft, the Linux community, etc.), and then making their findings public after a certain amount of time. If things work as they should, the security issue will be resolved before they share details on how to exploit the security flaw.

In a DDOS, numerous devices are used in a concerted effort to overwhelm on domain or one domain name server. The October 21 attack may have been pointed at Sony’s PlayStation services or at Dyn, but the ultimate impact was on every service using Dyn for DNS.

DNS has been compared to a phone book (remember those) with the domain name and IP address of every active domain on the Internet. When you type lowendmac.com into your browser’s address bar, your device connects to a router that talks to a domain name service that converts that text string into an IP address.

To avoid being overwhelmed, DNS caches search results, so it doesn’t have to make a fresh look for lowendmac.com every time someone connects to our server. It may cache that data for hours or days or even longer, something that can be specified by the domain owner.

Two Aspects of the Attack

Two things happened with the October 21 DDOS: First, the Mirai attack software was remotely installed on a huge botnet including not only personal computers but also devices such as routers, internet webcams, smart TVs, and internet connected fridges, sometimes call the Internet of Things.

Second, the attack took advantage of the way DNS works to force Dyn’s servers to do new lookups for seemingly legitimate domains. For instance, http://lowendmac.com/ and http://www.lowendmac.com/ are legitimate and should already be caches, but fake subdomains such as qwerty.lowendmac.com, abcdef.lowendmac.com, lowendmac.lowendmac.com, and so on are not legitimate. Problem is, the domain name system won’t have them cached, so it has to look them up in the Internet Phone Book. That takes time, and by creating tens or hundreds of thousands of fake subdomains and having thousands of devices doing it at the same time can quickly overwhelm a system not hardened against this kind of attack.

What Can I Do?

A lot of these bots on the Internet of Things got there because users never changed the default login information on their equipment. If you haven’t change the login info for your router, smart TV, internet camera, etc., you are leaving your hardware open to this kind of exploitation. First thing you need to do is change the default login credentials so botnets can’t get in easily.

The second thing is to look into other domain name services if you’re using the ones provided by your internet service or hosting service.

Free DNS Alternatives

Dyn is far from the only domain name server (DNS) system out there. OpenDNS and Google provide free DNS, and neither was impacted by the DDOS attack on Dyn. That doesn’t necessarily mean that you could reach the servers using Dyn, but you could access the rest of the Internet.

I’ve used OpenDNS for years, and it provides many options for filtering content, which can be especially helpful if there are youngsters in the home. Both OpenDSN and Google’s Public DNS tend to work more quickly than the DNS your internet service uses.

OpenDNS

To use OpenDNS, go to the network settings on your computer, mobile device, router, etc. and set the DNS server to these two numbers:

- 208.67.222.222

- 208.67.220.220

Public DNS

To use Google’s Public DNS, use these two numbers:

- 8.8.8.8

- 8.8.4.4

That’s all there is to it. Unless your device tells you otherwise, you shouldn’t even need to do a restart.

Timeline

- September 20-21, 2016: KrebsOnSecurity Hit with Record DDoS, Krebs on Security

- October 1, 2016: “Anna-senpai” publishes source code for Mirai botnet, Krebs on Security

- October 14, 2016: Heightened DDoS Threat Posed by Mirai and Other Botnets, United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team.

- October 21, 2016. DDoS on Dyn Impacts Twitter, Spotify, Reddit, Krebs on Security

Further Reading

- Mirai IoT Botnet: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know, Heavy, 2016.10.21

Keywords: #ddos #miraibotnet #dyndns

Short link: https://goo.gl/g6HhxY